23 January 1999

Source: The New York Times, January 24, 1999, p. AR 36

ARCHITECTURE |

|

A Le Corbusier Vision Blurred Over Time

Despite the idealism of its founders,

Chandigarh faces a squalid reality of environmental abuse, industrial

encroachment and illicit construction

|

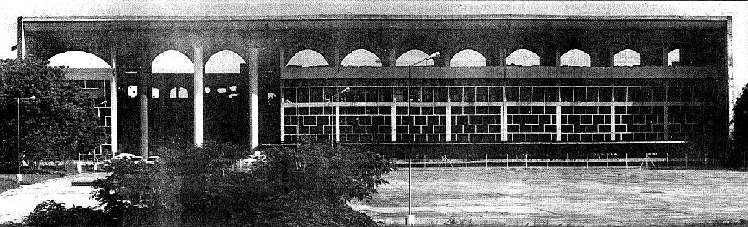

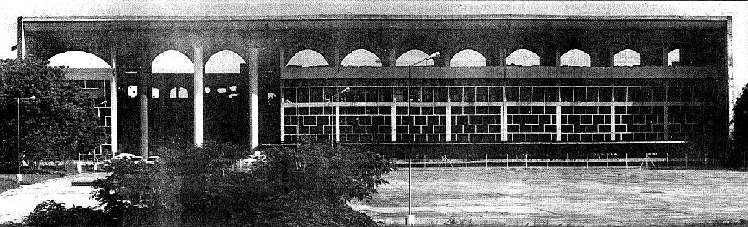

At Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab, the High Court (above) is part

of the government center designed by Le Corbusier. It is built of gray concrete,

occasionally braced by thin membranes of reinforced concrete.

|

|

By PATWANT SINGH

Patwant Singh was for many years the editor of Design magazine in New

Delhi. His forthcoming book, "The Sikhs," is to be published this fall by

Knopf.

NEW DELHI

THE city of Chandigarh owes its existence to India's first

Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. With Pakistan inheriting Lahore, capital

of the truncated state of Punjab, after India's 1947 partition, Nehru decided

to locate the world's finest architect to design a capital for the remaining

portion of Punjab. By 1950 the choice had fallen to the controversial Swiss-born

Le Corbusier, a resident of Paris since 1916.

Now, as the 50th anniversary of Le Corbusier's commission approaches, the

time seems apt to re-examine the success of his grand vision. Visually stunning,

Chandigarh has had to function as a real city in the teeming India of this

half-century. Has lt worked? What is the city like now? As with the Brazilian

capital of Brasilia in the Amawn basin, how has a city created in the mind

of an architect worked within the complexities of modern life?

Though excited by India's offer, Le Corbusier was reluctant to accept because

of his preoccupation with Europe's postwar reconstruction. But he agreed

to visit India after the Indian Ambassador in Paris, H. S. Malik, got France's

Minister of Culture, Andre Malraux, to intercede. Le Corbusier developed

a rapport with Nehru, and the Prime Minister's unstinting support for the

temperamental architect insured the construction of the city, to be built

in the Himalayan foothills 160 miles north of Delhi.

Chandigarh -- which gets its name from the Hindu deity Chandi, in whose memory

a temple exists nearby -- was a "first" for Le Corbusier, who had never had

an assignment of this magnitude before. While he was still to design a building

in the United States, India had asked him to create an entire city.

Le Corbusier, vowing to "make a plan which is simple," sketched out what

he had in mind: "A big village in burnt bricks. I will bring in air and keep

the sun god in control. A garden in every house. It will not be Paris, London,

New York but Chandigarh, the New City." Meeting for the first time at the

site of the new capital in February 1951, the architects and town planners

drew up initial plans in six weeks.

The team Le Corbusier assembled for the project consisted of his cousin Pierre

Jeanneret, a distinguished architect with whom he had worked from 1922 to

1939, along with an English couple, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew. Among the

young Indian designers involved were Urmila Chowdhury, Jeet Malhotra, Piloo

Mody, A. R. Prabhawalkar and Manmohan Sharma. But the design was largely

based on a proposal by Albert Mayer of New York, who had earlier been asked

to prepare a concept but who had withdrawn after his brilliant young assistant,

Matthew Nowicki, died in a plane crash.

The focal point in the final version was the Capitol, consisting of the State

Secretariat, the High Court, the Legislature and the Governor's House. (The

latter is still to be built.) A great avenue 300 feet wide connects the Capitol

to the other end of the city, while a similar avenue crosses it at right

angles and links the industrial zone, railway station and city center to

the university, museums and other educational and recreational areas.

The plan includes 29 self-contained Sectors (with provision for adding more),

each, according to Le Corbusier, "the container of family life." He maintained

that the idea for the rectangular Sector is derived "from an ancestral and

valid geometry established in the past on the stride of a man, an ox or a

horse, but henceforth adapted to mechanical speeds." So the city's roads

are designed to insulate Chandigarh's residents from fast-moving vehicular

traffic. "No house (or building) door opens on a thoroughfare of rapid traffic,"

he said.

In Le Corbusier's view, Chandigarh's eight categories of roads, from V-1

to V-8, would create "an extraordinarily clear vocabulary in all future

discussions related to town planning." The V-2's are the two 300-foot-wide

avenues that intersect in the heart of the city, while the V-1 connects

Chandigarh to other cities but does not pass through it. V-3's go around

each Sector but are reserved for fast-moving traffic. And so on down to the

V-8, which is designed for bicycle traffic.

His three buildings for the Capitol do not quite fit his concept. Instead

of a big village in burnt bricks, they are constructed in mass concrete,

gray in color, occasionally braced by thin membranes of reinforced concrete.

Their design exudes strength and self-confidence. The rough texture of the

concrete surfaces was obtained accidentally. Since large quantities of wooden

shuttering for poured concrete were unavailable, sheet-metal shuttering was

fabricated and the textures that emerged on removing it opened "a magical

door for modern architecture," said Le Corbusier, revealing "the accessible

splendor of reinforced concrete."

Le Corbusier sacrificed neither function nor form in these buildings. With

more than 5,000 employees working in the 800-foot-long, eight-story Secretariat,

two dramatically designed ramps allow office workers to walk up to their

floor in what he called "an optimistic procession, in a continuous flow .

. . the ramp being the predestined tool for the masses, the stairs being

the calamity of pompous academism." All the same, staircases and elevators

are provided throughout the building.

The Capitol complex has its critics. The architect Philip Johnson sees "no

possible relation physically" among the three principal buildings nor "any

possible relation of the government center to the city they are in.' Cities,

of course, take time to grow. One reason the complex lacks cohesiveness is

that its construction has never been completed. It could, no doubt, have

been placed nearer the city proper. Peter Blake, former editor of Architectural

Forum, said he 'couldn't help noticing how little Chandigarh seemed to reflect

the life of India's people." Perhaps, but the romantic idea of a 20th-century

city recreating the crowded, colorful and cacophonous bazaars and lanes of

cities built by the great Mughal emperor Shahiahan in the 17th century is

a bit unreal.

PEOPLE in Chandigarh do congregate and jostle in the shopping

centers and neighborhood markets in spaces that are better defined. The Capitol

complex and the people could be brought closer if the insecurities of the

politicians and administrators had not led them to fence its open spaces

with barbed wire and to place armed guards there. To infuse life, color,

vitality, movement and texture into a city is the task of an inspired government

and civic leadership; Chandigarh has lacked both.

Credit for recognizing the esthetic possibilities of bricks -- absent in

the Capitol complex buildings but imaginatively used elsewhere in the city

-- goes to Jeanneret. Jeet Malhotra, his assistant for many years, who went

on to become Punjab's Chief Architect, says: "Jeanneret greatly influenced

the use of brick in Chandigarh. Eighty percent of the houses built by the

government are in the low-income category and almost all of them are built

with hand-made, burnt bricks. He found their color and textures enchanting."

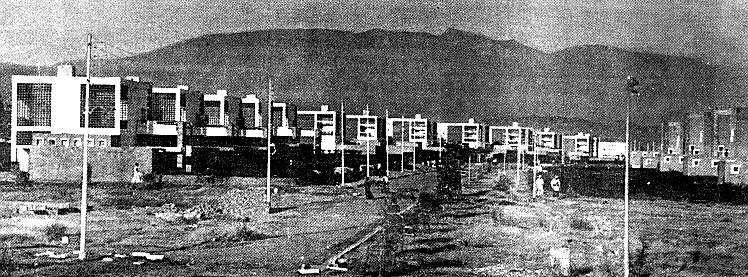

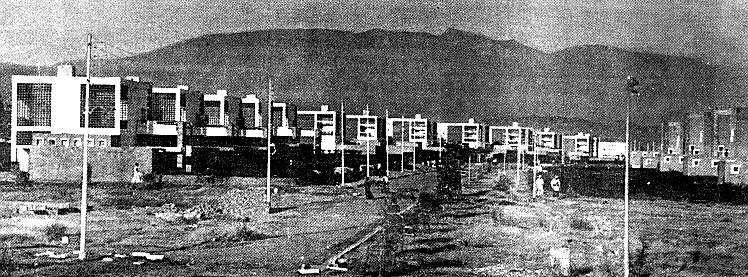

Government-employee homes, each with kitchen, bedroom, bathroom and

living area.Open spaces and shopping are nearby.

Houses for low-income groups are easily the best built in India in recent

times. Ashok Thapar, whose father was one of the officials who signed up

Le Corbusier, says: "My father would never tire of recalling how gratifying

it was to discover the enthusiasm stirred up by Chandigarh, at an altogether

unexpected level, among the lowest rung of government employees. A great

deal of thought and imagination went into insuring that each had a little

compound, a small kitchen, bedroom, bathroom and a separate living area,

together with open spaces and nearby shopping facilities."

Despite the legacy of Nehru's idealism and the creativity of its designers,

Chandigarh is an endangered city. Expedient politicians, ineffective

administrators and unprincipled business lobbies-whose numbers have grown

since the days of Nehruvian decencies-are destroying it. I saw evidence of

this everywhere during a recent visit: more slums, more unauthorized

construction, more violations of civil codes, more encroachments by industries,

more environmental abuse.

Anticipating these dangers, Chandigarh's founders had legislated the Capital

(Periphery) Control Act of 1952, which disallows major construction within

its 10-mile radius. Two flagrant violations by adjacent states were accepted

without a murmur in the 1960's by Chandigarh's administration, while lesser

infringements are routine.

The Punjab Government posed an even greater threat by trying to build a second

and bigger Chandigarh adjoining the first in 1994. In addition to local

resistance, 70 architects, designers, artists, writers and others from around

the world wrote to India's Prime Minister urging the Government to "make

a major effort to preserve and enhance this remarkable city" and professing

their admiration for a city worth "maintaining as a monument to some of the

ideals that have moved our century."

The signatories included Frank Gehry, Peter Blake, Ivan Chermayeff, Aiko

Miyawaki, Harry Seidler and George Heinrichs. Though construction was stopped,

the reprieve could be temporary. Given the bane of India's exploding population

and encroachments by new industries, the danger to Chandigarh is very real.

Planned for 500,000, its population now exceeds 850,000, with an expansion

to 1,260,000 expected by the year 2020.

Can Chandigarh's runaway growth be stopped? It can, if a new industrial town

is developed 70 to 80 miles away, if no new industries are allowed around

the city and if the Periphery Control Act is rigidly enforced. While this

presents a great challenge, it can be met if the political will to save

Chandigarh is forthcoming.